Pragmatic Institute Framework

using the community

Pragmatic Framework

Explore areas of the Pragmatic Framework.

Click on any of the boxes to see a description of that activity.

Discover problems in the market by interviewing customers, recent evaluators and untapped, potential customers. Validate urgent problems to show their pervasiveness in the market.

Understand why recent evaluators of the product did or did not buy and what steps they took in the buying process.

Articulate and leverage the organization's unique abilities to deliver value to the market.

Identify competitive and alternative offerings in the market. Assess their strengths and weaknesses. Develop a strategy for winning against the competition.

Inventory your assets (technical, skills, services, patents, other) and determine ways that they can be leveraged.

Market

Map needs with target markets and analyze the market segments to actively pursue. Ensure that the targeted segments are large enough to support the current and future business of the product.

Determine which channels best align with your markets' buying preferences.

Integrate products into a coherent portfolio of products focused on the market. Manage the portfolio like a "product" (business plan, positioning, buying process, market requirements and marketing plan).

Illustrate the vision and key phases of deliverables for the product. The roadmap is a plan, not a commitment.

Focus

Perform an objective analysis of a potential market opportunity to provide a basis for investment. Articulate what you learned in the market and quantify the risk, including a financial model.

Establish a pricing model, schedules, guidelines and procedures.

Determine the most effective way to deliver a complete solution to an identified market problem. Where you have gaps in your offering, analyze whether to buy, build, or partner to complete the solution for your market.

Monitor and analyze key performance indicators to determine how well the product is performing in the market, how it impacts the company operations, and ultimately, how it contributes to profit.

Focus your teams' creative spirit on solving market problems by leveraging your organization's distinctive competencies.

Business

Describe the product by its ability to solve market problems. Create internal positioning documents used to develop external messages focused on each key buyer or persona.

Understand and document the buyer's journey for the key segments and buyers we have identified.

Define the archetypical buyers involved in the purchasing of your products and services.

Define the archetypical users of your products or services.

Articulate and prioritize personas and their problems so that the appropriate products can be built.

Illustrate market problems in a "story" that puts the problem in context. Use scenarios are one component of requirements.

Manage proactive communications with relevant stakeholders from strategy through execution.

Planning

Articulate the strategies and tactics for generating awareness and leads for the upcoming fiscal period, including key programs and events with measurements and goals.

Define the specific plans and budgets for selling products and services to new customers.

Define the specific plans and budgets for ensuring customer loyalty, as well as selling products and services to existing customers.

Plan, execute and measure effectiveness of strategic launches.

Develop programs to raise the profile and awareness of your brand within strategic market segments to bring more prospects into your funnel.

Develop programs to move prospects quickly and effectively through the funnel, with the objective of turning prospects into satisfied customers.

Identify customers who are willing to give testimonials, case studies and references and amplify their voice in the market.

Measure and tune product marketing programs to ensure alignment with corporate goals.

Programs

Use your market knowledge to help sales align their selling process to the way the market wants to buy.

Develop relevant content to be used for all go-to-market channels and materials.

Create tools for salespeople focused on a specific step of the selling process.

Design and deliver training programs to help the sales channels focus on how to sell the product, not how to use it.

Enablement

Provide needed market and solution information to support internal and external marketing programs.

Provide needed market and solution information to support the operations group.

Provide needed market and solution information to support marketing events such as conferences, trade shows and webinars.

Provide needed market and solution information to support channel opportunities and activities.

Support

Get your copy of The Pragmatic Framework

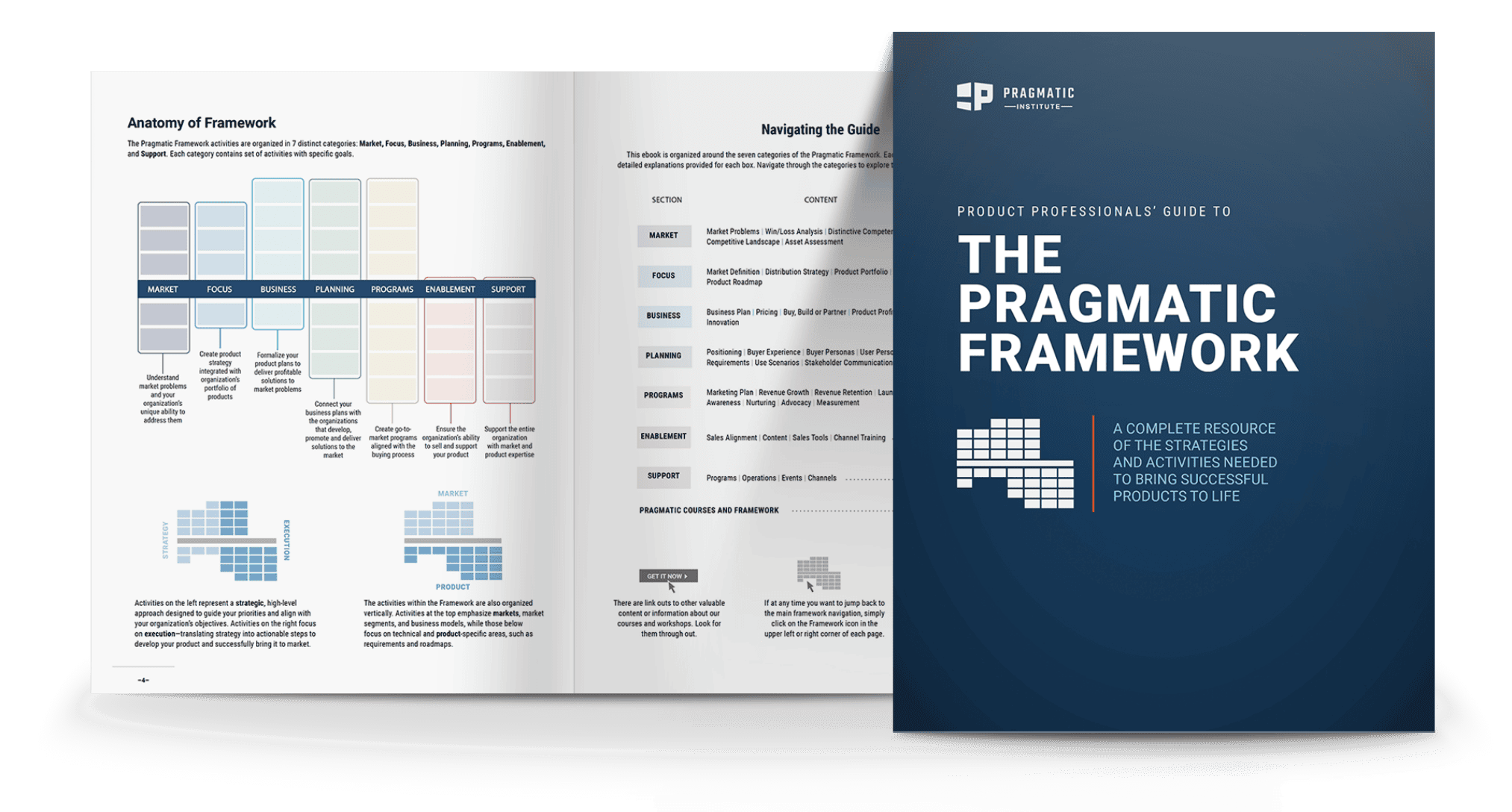

Pragmatic Framework, once popularly called the Pragmatic Marketing Framework, consists of 37 boxes arranged in 7 categories. Each box represents key activities and responsibilities across the entire product lifecycle, helping teams understand what to focus on at each stage to create successful, market-driven products. Together, they provide a comprehensive roadmap that aligns teams with market needs and business goals.

By following the Framework, companies can ensure their products are strategically positioned for success from concept to launch.

Explore eight essential concepts from the Pragmatic Framework

For a complete breakdown of all framework components, download the eBook.