Many organizations struggle to define their products. They have complex products that do a lot of different things for a lot of different people, making it hard to say what the product really is, what value it delivers and to whom.

Why is this bad? In a word, focus.

The more things a product does for more people, the more complex it becomes, the harder it is to use and the harder it is to deliver. Complex products that are burdened with features no one understands—but no one can kill—create organizational complexity, increase costs and result in baffling products that frustrate customers.

To cut through this, my simple definition of a product is “a vehicle for delivering outcomes to some group of people.” With luck, these outcomes achieve value for the user as a result of a positive change. The customer (or user) finds value in doing things they couldn’t before or experiencing things they hadn’t experienced before.

The best products deliver a relatively small set of positive outcomes to a group of people with a common set of needs. To illustrate the importance of simplicity, consider when you’re preparing dinner and you need to cut some vegetables. Which will better meet your needs: a multi-tool pocketknife or a chef’s knife? And which knife would you prefer if you’re hiking in a wilderness of unknown conditions?

Different people have different needs in different circumstances—each of which is served by different products that deliver different outcomes. A lot of product professionals talk about “the customer” as if there is such a thing as a single user with a single set of needs. This language prevents people from seeing who really uses the product and why.

Going back to the knife example, I have both types of knives, so I am “the customer” for both. But focusing on all my needs at once is confusing. Instead, focusing on my desired outcomes under specific conditions yields better insights:

- I sometimes need to slice and chop a lot of different vegetables to prepare different meals

- I sometimes need different tools to solve different problems in various situations; but, because I can’t predict these situations, the tools need to be portable but only need to perform adequately

Outcomes focus on the end result and the context in which I want to achieve them, not the means by which I achieve them.

Simpler Products Are Easier to Develop and Use

Many organizational scaling problems come from large, complex, and poorly focused products. The more a product does, the more people need to be involved in its development. As a product grows beyond something a single team can develop, the cost and complexity of delivering that product increase exponentially.

Rather than trying to figure out how to scale product development, first, try simplifying a complex product into two or more simpler ones. If the product is getting too complicated, if it delivers this outcome to one group of people, thatoutcome to another group, and another outcome to a different group, it might be time to split it into several products.

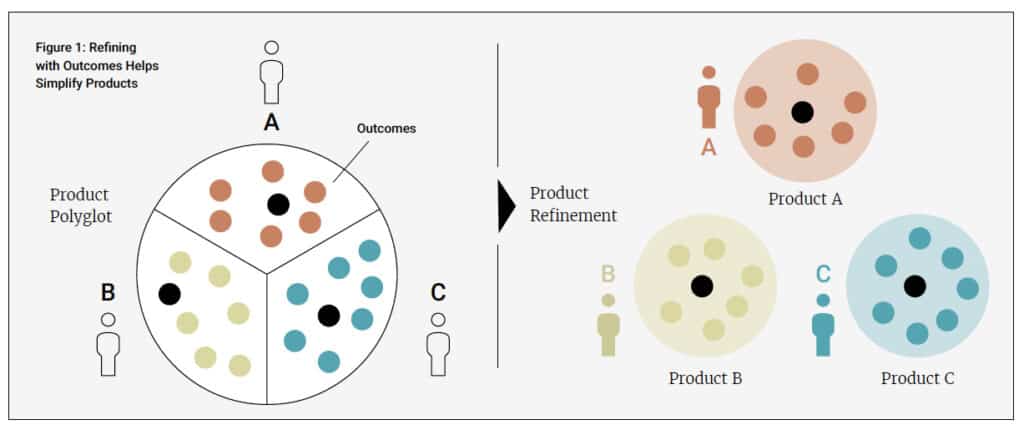

For example, in Figure 1, “Product Polyglot” does a lot of different things for different people in different situations (by way of metaphor, it speaks in different languages to different groups of people). There also are some shared capabilities (the black dots) that benefit all users. By splitting Polyglot, each product becomes simpler to develop and use. There is a little complexity to manage the common capabilities in each, but there are ways to manage this—and using shared components is just one.

By dividing Polyglot, each product serves its customers in the simplest possible way. Each product development team can get to know their customers and their unique needs more intimately, thus producing better results.

Of course, there are some products that, if they delivered only a single outcome, they would be less usable. For example, think of using a single smartphone clock app (rather than separate apps) that tells your current time as well as the time in various time zones and has an alarm clock, stopwatch and timer.

An ideal product bundles related outcomes because people tend to think of them in similar ways. Likewise, that ideal product may be less costly to produce because similar expertise is needed to produce it.

The Importance of Architectural Finesse

There is a good way and a bad way to split a big product into smaller ones. The bad way clones the big product into different versions, each of which is a partial copy of the original. The problem with this is that you now have several versions of the same code (or components for physical products), and each must be maintained.

Products become large because organizations don’t have good ways to manage shared components. They understand that maintaining multiple versions of the same thing is bad, so they choose the evil they consider less bad: bloated products.

But there is a better way.

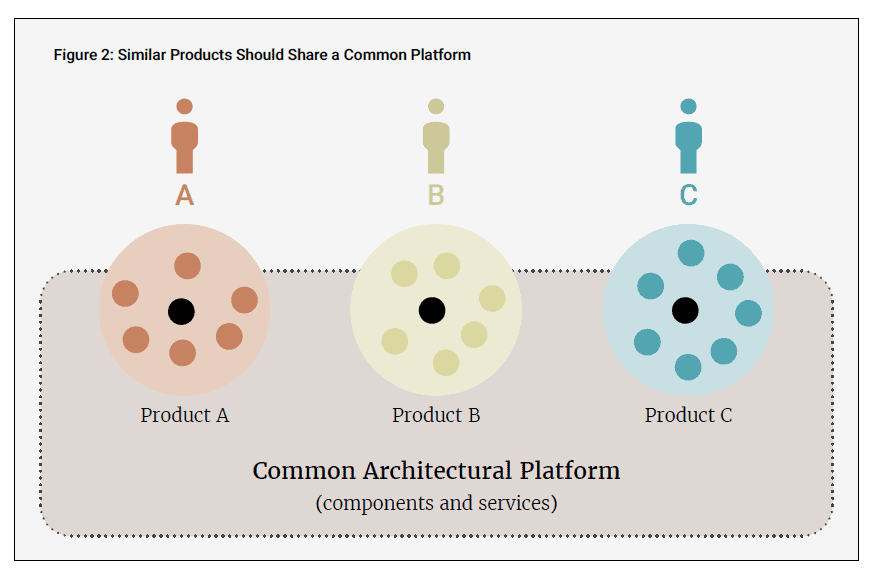

Figure 2 shows the three refined products from Figure 1 sharing a common platform architecture that consists of common components and/or services that each product uses to deliver its unique outcomes. The platform is almostlike another product, except it has no real customers—it exists solely to serve the needs of the products it supports.

The best way to manage this is as a set of versioned services that are collectively managed by the product teams. If one team needs a new service, it lets its peer teams know what it’s doing. If another team needs something similar, they can collaborate to build it. If one team needs to add something to an existing service or change the way a service works, it creates a new version of the service rather than potentially breaking that service for peer teams.

This approach to managing the platform works better than treating it as a product with its own team, as having one team own the platform creates bottlenecks for the “client” teams. The platform team would have to coordinate a lot with the client teams, and the client teams would have to wait on the platform team. Even worse, being one step removed from the real problems the platform is trying to solve, the platform team is less capable of really meeting the product teams’ needs.

Simpler products backed by a shared platform enable each product team to rapidly respond to customer feedback or competitor shifts. Product teams are freed from the complexity of planning and coordinating large product releases, and they escape the complex political (and seemingly unavoidable) feature-negotiation process that large products seem to require.

The cost of this speed and flexibility is that the organization must learn to master the techniques of managing a shared set of services without creating a new team or organization to manage those services.

Simplify to Scale

Large products are challenging to deliver. Sometimes products are large because the problems they solve are inherently complicated (think of an airliner). But sometimes they are large simply because of a lack of focus. Refining products based on desired outcomes provides organizations with a tool to reduce products to their simplest form and avoids complex but unnecessary scaling approaches.

Author

-

Kurt Bittner is vice president of enterprise solutions at Scrum.org. Connect with him on LinkedIn.

View all posts